Skills (What you can do!)

- All skills needed!!

Functions (What role you would play!)

You may have 1 or more of these skills!

- Fundraising - storytelling, strategy, communications, budgeting, networking, relationship building, research, project management

- Policy - research, communications, legal, institutional development, relationship building, politics

- Institutional development - research, governance, relationship building, politics

- Economic development - economic modelling, industrial development, market systems strategy, welfare

- Social welfare - advocacy, social welfare subsidies, charity work,

- Private sector development - business innovation, enterprise development, enabling environment, entrepreneurship, taxation and legal

- Marketing and retail - commerce, business management, sociology, psychology, policy and/or network development

- Operations - logistics, network management, project management, finance, and/or results measurement

- HRM - sociology, psychology, training and development, and/or team building

- Finance - finance, strategy, M&E, project management, and/or legal

- Results measurement - finance, strategy, project management, and/or research

New Trends (Where you might position yourself!)

- Market-based development

- Socialist market systems

- Social welfare

- Ethical business

- Fintech

- Behaviourial sciences

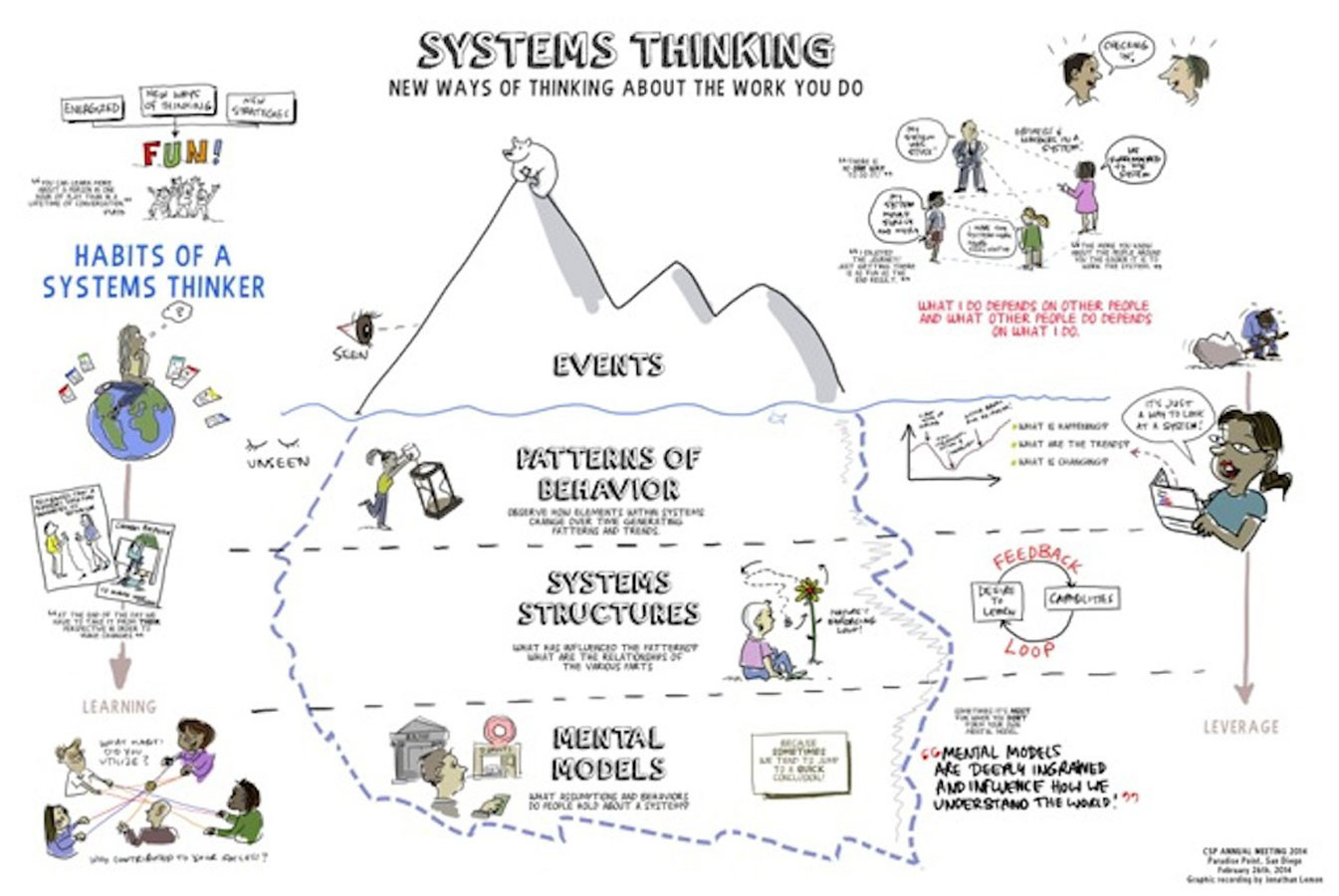

- Systems change

- Resilience

- Conflict

- Livestock

- Healthcare

- Climate and the natural environment

- Informal sector

- NGO organisational development

- Foundation funding

- Be different - If you have good ideas that seem too out-of-the-box for traditional work, this could be the right time to build a skills around it and offer that skill to the development space

- Look deeper than large institutions - If you want to learn on the job, develop tangible skills and be part of an impactful project, start at the field and work upwards

- Competences are important - teamwork, patience, time management, critical thinking, adaptability, focus and determination