Let us build a new world. Let us move to a new solar system and build a new way of living. Let us do it all again. Let us think about society, markets, systems thinking, behaviour change, people, philosophy...

Showing posts with label market. Show all posts

Showing posts with label market. Show all posts

Saturday, 10 September 2016

Thursday, 23 June 2016

Marjorie Kelly on the Emergent Ownership Revolution

Do you need something more tangible to use when talking about social business?

Is the 'social purpose' argument a bit thin for you?

According to Marjorie Kelly in Towards Mission-Controlled Corporations: Extractive vs Generative Design there are 5 elements of a generative ownership-driven design framework for social businesses:

- Membership – How can we have the right people forming part of the business? How can they contribute to the running of the business? What roles and authority can they have?

- Purpose – What purpose can a business have beyond profit-making for shareholders? What problems might it solve? How is 'wealth', and value spread within the local community?

- Governance – Who is the board? Who does the board answer to?

- Finance – Where does the money come from? Where does it go? How does it circulate through the business? How does it generate wealth and value?

- Networks – How does the business get access to goods, services, information? How might the exchange be carried out? How might it be non-financial? How might it reach beyond typical boundaries e.g. geography?

Saturday, 2 April 2016

Will Starbucks food donations encourage local restaurants and shops to do the same?

Interesting question. Possibly. But as said below by a previous poster the value chain and business processes at large food restaurants look different from those at small restaurants and thus the opportunity for surplus (and thus donations) is different.

Let me add one thought that sprung to mind. In my experience, the other factor that affects the flow of surplus food to the people who need it are the intermediaries in between. For example, small restaurants are not normally able to afford to send/deliver/transport food to charities outside of a couple of miles and small charities are not normally able to absorb this cost either. One idea is that services spring up to help this process/fill a gap. Maybe a group of restaurants band together to hire a van or a group of charities do that ... or even a separate intermediary (maybe... a neighbourhood support scheme paid through by the local authority or even people/citizens/charitabl

So, we might see that maybe instead of giving money to charity, people give money in other ways to help restaurants get their food to people who need it.

Originally posted on Quora here

Friday, 1 April 2016

Has anyone applied systems thinking to international development?

The short answer is Yes!

The longer answer is that this area is still undergoing an attrition and evolution with people in the sector trying to shape what this means for them and their work. There is a real dearth of good M&E/impact evaluation support for systems thinkers in development, which makes the work harder. There are some organisations that addressing this issue head on and are moving away from M&E and towards more knowledge, learning and practice. To do this requires building the capacity within field teams, management, senior management and also, with donors.

For me, the most interesting thing is how systems thinking principles are used effectively. The aim should be to help developing countries determine what kind of system they want to have and what people will want to do in the system. A big danger to the space that in our attempts to 'bring about a better way of doing things', we determine what the system should look like *for* countries and we hard code these principles activities and behaviours *for* people. Moreover, integrative, participatory and democratic approaches for systems thinking are often just not enough because it can set up a situation where there is still a dominant thinking that others are being encouraged to conform to or align with.

In a nutshell, systems thinking for development cannot be the end-goal. It should be a starting point to think about doing development differently and better.

Originally published on Quora here

Wednesday, 9 December 2015

What types of careers are there in international development?

Skills (What you can do!)

- All skills needed!!

Functions (What role you would play!)

You may have 1 or more of these skills!

- Fundraising - storytelling, strategy, communications, budgeting, networking, relationship building, research, project management

- Policy - research, communications, legal, institutional development, relationship building, politics

- Institutional development - research, governance, relationship building, politics

- Economic development - economic modelling, industrial development, market systems strategy, welfare

- Social welfare - advocacy, social welfare subsidies, charity work,

- Private sector development - business innovation, enterprise development, enabling environment, entrepreneurship, taxation and legal

- Marketing and retail - commerce, business management, sociology, psychology, policy and/or network development

- Operations - logistics, network management, project management, finance, and/or results measurement

- HRM - sociology, psychology, training and development, and/or team building

- Finance - finance, strategy, M&E, project management, and/or legal

- Results measurement - finance, strategy, project management, and/or research

New Trends (Where you might position yourself!)

- Market-based development

- Socialist market systems

- Social welfare

- Ethical business

- Fintech

- Behaviourial sciences

- Systems change

- Resilience

- Conflict

- Livestock

- Healthcare

- Climate and the natural environment

- Informal sector

- NGO organisational development

- Foundation funding

- Be different - If you have good ideas that seem too out-of-the-box for traditional work, this could be the right time to build a skills around it and offer that skill to the development space

- Look deeper than large institutions - If you want to learn on the job, develop tangible skills and be part of an impactful project, start at the field and work upwards

- Competences are important - teamwork, patience, time management, critical thinking, adaptability, focus and determination

Saturday, 5 December 2015

What does it mean to do ethical business in apparel?

What value do ethical standards bring to the fashion industry?

What does it mean to be ethical in fashion ?

What is the business case for ethical fashion?

---

http://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/aug/10/lithuanian-migrants-chicken-catchers-trafficked-uk-egg-farms-sue-worst-gangmaster-ever

http://source.ethicalfashionforum.com/article/recycling-on-the-high-street-3-different-approaches

What does it mean to be ethical in fashion ?

What is the business case for ethical fashion?

- Product development that sources and uses raw materials according to sustainability regulations/norms/codes/standards/values in the industry

- Product design that reflects stories from different people and different culture (i.e. non-normative, beyond the Western beauty ideal) and in a way that respects ownership and that protects against cultural appropriation for profit

- Innovation based on participative collaboration that understands power structures and control/equality/equity issues

- Ensuring that wage payments, work health and safety conditions and regulations are observed, external audits and inspections are supported and violence and illegal practices are addressed through a fair justice system (Guardian)

- Working with producers and suppliers in developing countries: meeting regulations and codes and respecting power imbalances in ethical management styles and monitoring systems

- A systemic approach to certification/regulations/norms/codes/standards to bring about sustainability and scale and builds on the successes of supply chain strengthening (multi-stakeholder governance, transparency, independent verification, and third party chain of custody) (Business Fights Poverty)

- Creating a demand for ethical fashion by using multi-channel retail opportunities including pop-ups to showcase the brand the product and the story

- Ensuring that the pricing model allows producers and suppliers to be paid a living/decent wage even when it means charging the retailer or consumer a few pence more. The recent example of dairy farmers in the UK removing milk from supermarket shelves in an attempt to sell it directly to the consumer to get a better price.

- Understanding that in fashion there is economic value to the 'story' in the same way that any brand builds equity - through rational, emotional and behaviourial consumer analysis

- The impact on retail pricing - what is the market willing to pay?

- Businesses that 'work in Africa' do not automatically mean social enterprise or ethical sourcing

- Making your claims of ethical business practices credible and possible to observe and verify. Consumer driven - Mintel found that half of those surveyed said they would only pay more for ethical products if they understood clearly where the extra money went, and 52 per cent said they found information about which foods are ethical confusing (Supplymanagement.com)

- Working on textile waste to minimise, recycle, reuse, upcycle, upgrade, re-configure, re-integrate, and more (The Ethical Fashion Source)

---

http://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/aug/10/lithuanian-migrants-chicken-catchers-trafficked-uk-egg-farms-sue-worst-gangmaster-ever

http://source.ethicalfashionforum.com/article/recycling-on-the-high-street-3-different-approaches

Sunday, 22 November 2015

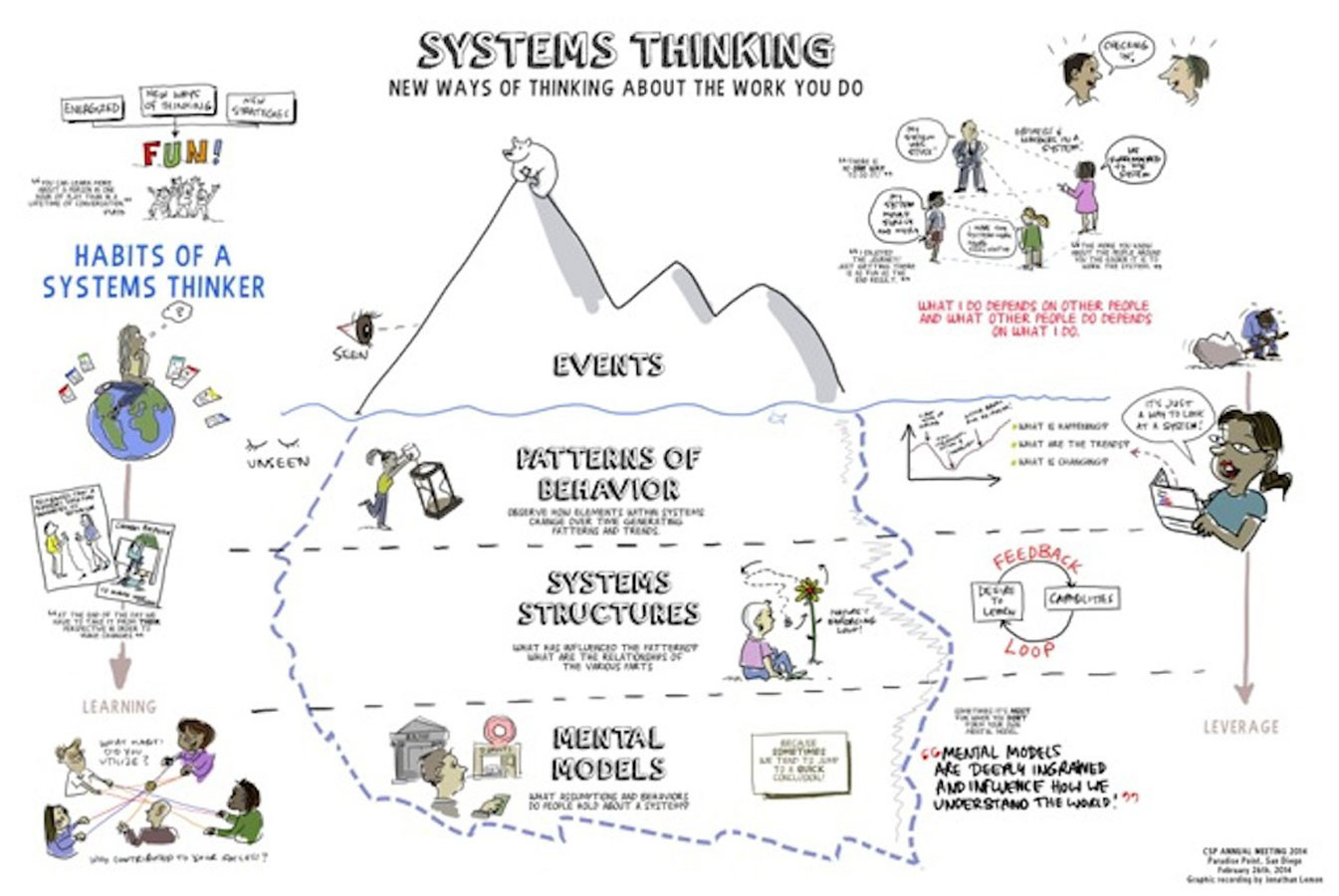

An illustration on mental models for systems thinking

The graphic was originally found on Twitter posted by Amy Koo @awykoo, who had come across it at a sustainability and systems workshop in November 2015: http://watersfoundation.org/category/newsletter-archives/march-2014/

Thursday, 12 November 2015

RCTs in poverty reduction and development: why are some practitioners abandoning RCTs?

This blogpost about ethics in international development is about a randomised control trial (RCT) in Kenya. In the experiment, some households in Kenya were given unconditional cash transfers of either USD 404 or USD 1525. The researchers found, unsurprisingly, that the lucky ones were happier and that their unlucky neighbours were unhappy. The paper is aptly titled “Your Gain is my Pain”.

Most importantly, however, the blogger reflects on why this type of research is done at all: "Am I the only one to think that is not ethical dishing out large sums of money in small communities and observing how jealous and unhappy this makes the unlucky members of these tight knit communities?"

For myself, as a development practitioner with a systems thinking perspective, RCTs can come across as having very limited usefulness and application. They can also be quite machine-based: they either choose to wilfully ignore human behaviour or they simply limit their interactions with other disciplines (psychology, sociology, anthropology) so that they can create more simple hypotheses. Thus, it is felt that the applicability of an RCT for complex problems (such as systemic poverty) is limited.

The RCT we have seen from Kenya seems to fall into that trap too. This RCT seems to need to test the notion that poor people in Kenya might not exhibit the same reactions and behaviours as other people. As if the nature of the human condition (in Africa) is under exploration. To me, this is strange and feels like the original hypotheses might have been drastically distilled and reduced down to overly simplified thoughts.

I wonder how the findings would actually be useful to policy and projects. Who might need proofs from an RCT that Kenyans are like any other human being? How could such research be useful for development planning at an economic or social level? Why is the notion that proving that desperation, jealously and unhappiness occurs among very poor people is valuable? I would also wonder what long-lasting impact this type of research would have on social relationships in the communities in the future.

Globally, there is a large community of development practitioner who feel that RCTs in poverty interventions are not ethical and not useful. From my conversations with them, they make the following points:

Most importantly, however, the blogger reflects on why this type of research is done at all: "Am I the only one to think that is not ethical dishing out large sums of money in small communities and observing how jealous and unhappy this makes the unlucky members of these tight knit communities?"

For myself, as a development practitioner with a systems thinking perspective, RCTs can come across as having very limited usefulness and application. They can also be quite machine-based: they either choose to wilfully ignore human behaviour or they simply limit their interactions with other disciplines (psychology, sociology, anthropology) so that they can create more simple hypotheses. Thus, it is felt that the applicability of an RCT for complex problems (such as systemic poverty) is limited.

The RCT we have seen from Kenya seems to fall into that trap too. This RCT seems to need to test the notion that poor people in Kenya might not exhibit the same reactions and behaviours as other people. As if the nature of the human condition (in Africa) is under exploration. To me, this is strange and feels like the original hypotheses might have been drastically distilled and reduced down to overly simplified thoughts.

I wonder how the findings would actually be useful to policy and projects. Who might need proofs from an RCT that Kenyans are like any other human being? How could such research be useful for development planning at an economic or social level? Why is the notion that proving that desperation, jealously and unhappiness occurs among very poor people is valuable? I would also wonder what long-lasting impact this type of research would have on social relationships in the communities in the future.

Globally, there is a large community of development practitioner who feel that RCTs in poverty interventions are not ethical and not useful. From my conversations with them, they make the following points:

- In many RCTs, an assumption is made that the the groups will not be communicating with each other. However, it is actually very difficult to have demarcated and clear boundaries for the treatment groups to be adequately isolated. People talk. Information can flow through multiple channels and through multiple mechanisms (face-to-face, mobile phone, internet, etc) across groups, geographies, social hierarchies, institutions, etc.

- In RCTs, people might be very desperate because of the psychological and social impact of poverty and crisis. In this case all the RCT does is exacerbate that desperation and exacerbate those behaviours that present themselves when people are in desperate situations. The results are therefore naturally biased and skewed and outlying when compared to any group at any point in time. This is not adequately recognised in RCTs and thus not at all reflected when RCTs attempt to influence policy and project applications.

- Over time, the RCT can have a lasting negative impact. Those RCTs which test the type of reactions as the one featured here in Kenya - jealousy and unhappiness - can damage social relationships between individuals and groups even after the trial has ended. Real people are not as adept to switching off their pain and trauma (and any additional feelings of betrayal, anger, envy, frustration, etc.) as machines might be able to!

Monday, 24 August 2015

What are some useful indicators of systemic change?

What is systemic change?

- A measurement of the change in the rules that govern the system and that affect how actors/agents behave and function. From an economic perspective, this means going beyond the conception of people as 'rational individuals' and incorporating a better understanding of social constraints that lock us in to our patterns of consumption.

- The relationship between certain types of 'resilience finance' and the ability to confront shocks and disasters at individual level, household level, business level, industry level and across social networks and political positions

- A measurement of 'subjective resilience' at household level to better understand the ability to "anticipate, buffer and adapt to disturbance and change"

- Developed by looking at synergies between the development, business and economics fields of study to better frame measurements of systemic change. Bringing together traditional nonprofit measurements around poverty and impact with typical business and social enterprise measurements of efficiency and effectiveness with typical economic measurements, such as tax revenues, job creation, labour income, for deeper systemic measurement, such as increase in business-to-business services, change in investment patterns towards long-term customer relationships and emergence of new market-based products and services that respond to pro-poor needs.

- A recalibration of the equilibrium. Moving systems from unjust to just, marginalisation to inclusion, structural disadvantages to systemic advantages (gender), traders to value creators, short-term transactions to long-term relationships and incremental shifts [in markets] to transformations and revolutions,

Saturday, 22 August 2015

What does a market system specialist like me do?

Economic Development

- Develop retail networks in developing countries to get products and services in the hands of low-income marginalised consumers

- Help aid programmes do more systemic social welfare through systemic safety net programmes

- Improve the enabling environment for MSMEs and the informal sector

Social Business and CSR

- Look at supply chain interventions that go beyond the value chain approach and take more of a systemic perspective that actually deliver benefits to poor farmers

- Identify different areas where CSR can be better programmed by way of a market systems approach

- Integrate the private sector into market systems approaches that have historically focused on socialist mechanisms (large State, community associations, NGOs)

- Work with system actors to identify areas where market systems development will make a difference

Behaviour Change

- Train practitioners on behaviour change and behaviour change methodologies to help projects deliver systemic solutions

- Design behaviour change tools to improve the adoption and commitment of poor people to long terms savings and investments practices

Labels:

Africa,

apparel,

behaviour,

business,

consumer,

economics,

health,

ICT,

incentives,

informal,

innovation,

learning,

market,

prejudice,

resilience,

retail,

sustainability,

systems,

transformation

Tuesday, 11 August 2015

The systems for welfare and safety net programmes

How are welfare and social safety net systems set up?

Broadly speaking and quite simply, welfare and benefits help people through poverty as well as respond and be resilient to unexpected external shocks, such as macroeconomic downturn and job loss, sickness and injury, and other disabilities. Welfare also helps people grow their financial and asset base and are used to supplement incomes that are considered below living wage. Welfare can also help pay for supplementary services to people overcome poverty, respond to shocks and/or grow their asset base, such as childcare or energy subsidies.

Conversely, tax systems are used to generate income in order to redistribute to welfare recipients. Tax can be applied to incomes (and conversely tax can be reduced on low incomes and personal allowance thresholds). Tax can be applied to goods and services deemed harmful to other people and the environment such as cigarettes. Tax incentives (or tax-free activities) can be applied to goods and services deemed beneficial to other people and the environment such as solar panels for household roofs.

Welfare budget - The welfare budget is formed through amount raised in taxes and more precisely, the proportion of tax income allocated to the welfare system. Who decides this proportion? How does this money get allocated? Does the amount reflect the needs of the benefit claimants within the system? According to Open Democracy: "Benefit levels in Britain reflect political decisions on the amount governments in Britain have been prepared to spend, not the total of claimants’ needs."

Welfare eligibility criteria - There are several different categories of eligibility criteria to be able to clam welfare, such as time in work, dependents, length of residency. There are also different categories of benefit types from job seeker support, to housing to sickness to occupational injury. The specific criteria will differ in different countries. Above all, claiming benefits is not an easy task for local claimants or those from elsewhere classified as migrants or immigrants. And certain welfare opportunities are not included in the benefits system because they are public goods (from clean air to access to a universal healthcare system that treats personal injury and illness especially those that are communicable, contigious and treatable) (BBC News)

Multi-territorial welfare system - Across integrated trade and economic zones (where integration includes policies and regulations as well as social networks, culture and learning), such as the European Union (EU), it was found that migrants from wealthier countries (like the UK) have the power to claim benefits from across the water, in other equally wealthy or even less wealthy countries. At times, the number of Britons claiming welfare in the EU can be larger than 'EU migrants to the UK claiming welfare in the UK' (IB Times and the Guardian)

Changes to the welfare system - Changes to the amount in the welfare system (taxation) and who gets them (welfare recipients) are brought about by those operating within the system itself. The Government may seem to have decision-making power but what analysis do they do to make decisions and who does the research? In some cases, the EU can put pressure on member states to make welfare system changes (Social Europe)

Factors that affect the ability of a welfare system to work

---

https://www.opendemocracy.net/can-europe-make-it/charlotte-rachael-proudman/welfare-benefits-are-calculated-by-political-objective

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-25134521

http://www.ibtimes.co.uk/britons-claiming-benefits-across-eu-outnumber-immigrants-getting-welfare-uk-1484091

http://www.socialeurope.eu/2015/02/welfare-union/

Broadly speaking and quite simply, welfare and benefits help people through poverty as well as respond and be resilient to unexpected external shocks, such as macroeconomic downturn and job loss, sickness and injury, and other disabilities. Welfare also helps people grow their financial and asset base and are used to supplement incomes that are considered below living wage. Welfare can also help pay for supplementary services to people overcome poverty, respond to shocks and/or grow their asset base, such as childcare or energy subsidies.

Conversely, tax systems are used to generate income in order to redistribute to welfare recipients. Tax can be applied to incomes (and conversely tax can be reduced on low incomes and personal allowance thresholds). Tax can be applied to goods and services deemed harmful to other people and the environment such as cigarettes. Tax incentives (or tax-free activities) can be applied to goods and services deemed beneficial to other people and the environment such as solar panels for household roofs.

Welfare budget - The welfare budget is formed through amount raised in taxes and more precisely, the proportion of tax income allocated to the welfare system. Who decides this proportion? How does this money get allocated? Does the amount reflect the needs of the benefit claimants within the system? According to Open Democracy: "Benefit levels in Britain reflect political decisions on the amount governments in Britain have been prepared to spend, not the total of claimants’ needs."

Welfare eligibility criteria - There are several different categories of eligibility criteria to be able to clam welfare, such as time in work, dependents, length of residency. There are also different categories of benefit types from job seeker support, to housing to sickness to occupational injury. The specific criteria will differ in different countries. Above all, claiming benefits is not an easy task for local claimants or those from elsewhere classified as migrants or immigrants. And certain welfare opportunities are not included in the benefits system because they are public goods (from clean air to access to a universal healthcare system that treats personal injury and illness especially those that are communicable, contigious and treatable) (BBC News)

Multi-territorial welfare system - Across integrated trade and economic zones (where integration includes policies and regulations as well as social networks, culture and learning), such as the European Union (EU), it was found that migrants from wealthier countries (like the UK) have the power to claim benefits from across the water, in other equally wealthy or even less wealthy countries. At times, the number of Britons claiming welfare in the EU can be larger than 'EU migrants to the UK claiming welfare in the UK' (IB Times and the Guardian)

Changes to the welfare system - Changes to the amount in the welfare system (taxation) and who gets them (welfare recipients) are brought about by those operating within the system itself. The Government may seem to have decision-making power but what analysis do they do to make decisions and who does the research? In some cases, the EU can put pressure on member states to make welfare system changes (Social Europe)

Factors that affect the ability of a welfare system to work

---

https://www.opendemocracy.net/can-europe-make-it/charlotte-rachael-proudman/welfare-benefits-are-calculated-by-political-objective

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-25134521

http://www.ibtimes.co.uk/britons-claiming-benefits-across-eu-outnumber-immigrants-getting-welfare-uk-1484091

http://www.socialeurope.eu/2015/02/welfare-union/

Wednesday, 22 July 2015

Article - In health, let countries run their own programmes and take a systems perspective

A nice blog on lessons learnt in global health. Advice? Let poor countries run their own programmes and take a systems perspective ...

This blog was originally published here on the Guardian website.

This blog was originally published here on the Guardian website.

Lessons in global health: let poor countries run their own programmes

In 2008, Square Mkwanda found himself in a quandary: international pharmaceutical companies had just donated millions of dollars worth of drugs to treat Neglected Tropical Diseases (NTDs) in his native Malawi but the civil servant had no money to distribute them and they were stockpiling in the ministry of health’s warehouses. “I thought, what am I going to tell pharmaceutical companies? That I let billions of kwachas’ [Malawi’s currency] worth of drugs expire because we couldn’t spend just a few millions to distribute them?”

So he talked to his minister of health and they managed to free up enough funds to distribute the drugs in eight districts. By 2009, the distribution programme had reached all 26 districts and was entirely funded by Malawi. Seven years on, Mkwanda, who is the lymphatic filariasis (LF) and NTD coordinator at Malawi’s ministry of health, proudly announced that Malawi has interrupted transmission of LF (pdf), the second country in Africa to do so.

Leadership like that demonstrated by Malawi was one of the key themes in thethird progress report of the London declaration on NTDs, produced by the consortium Uniting to Combat NTDs and released at the end of June. The report said: “Endemic countries are demonstrating strong ownership and leadership, in variable financial, political and environmental circumstances, to ensure their NTD programs are successful in meeting 2020 targets. Countries are achieving elimination goals, more people are being reached, and the drug donation program for NTDs, the largest public health drug donation program in the world, continues to grow.”

In the wake of the Ebola crisis and in preparation for the sustainable development goals, these success stories are important best practice examples for the global health community as it rethinks how to effectively deliver sustainable programmes. Recognising the opportunities for lessons learned, the World Health Organisation called the elimination and control of NTDs a “litmus test for universal health coverage (UHC)” – one of the targets of the new development agenda.

Other countries are joining Malawi to take charge of their public health initiatives. Bangladesh, the Philippines and India are now financing 85%, 94% and 100% of their NTD programmes respectively. Motivated by growing evidence of the impact of NTDs on child development and productivity (and as a result on economic growth) 26 endemic countries met in December 2014 to sign the Addis Ababa NTD Commitment, in which they agreed to increase domestic investment for NTD programme implementation. The Addis commitment was an initiative of Ethiopia’s minister of health Kesetebirhan Admasu. Explaining why more governments are showing interest in this work, Admasu said: “NTDs are not only a health agenda, but a development agenda too, for which the poor pay the highest price.”

These country-owned programmes come in different guises but at the heart of every successful one is an integrated, multi-sectoral approach. Ethiopia for instance requires that every partner working on trachoma implement the fullSAFE strategy – Surgery, Antibiotics, Facial Hygiene, Environmental Improvements – and not just the ‘S’ or ‘A’, on which development programmes tend to focus.

Brazil decided to include NTDs in its national poverty reduction programme, which has other development targets such as education, water and sanitation. Municipalities, who implement the programme, are given free rein to tailor interventions to best suit their circumstances (a peri-urban municipality would have different issues from an Amazonian location for instance).

Other countries used the single funded programme they had – onchocerciasis in Burundi’s case – as the building block to a fully integrated, multi-disease programme. There the ministry of health put in place a dedicated NTD team and worked with national and international partners to build a national programme that has been immensely successful. By end of the programme in 2011, national prevalence of schistosomiasis had been reduced from 12% to 1.4%.

Country ownership doesn’t just encourage policymakers to come up with strategies to reach their entire populations with health interventions but it also enables them to practice good resource management. Mkwanda says that NTDs brought good discipline at the ministry of health. “As with NTDs, we sit and budget. And we do not segregate diseases – integration isn’t just for NTDs, it’s for the whole essential care package.”

The story gets even better as countries in the global south, such as Brazil and Nigeria, are not just coming up with their own programmes but also funding others’. Marcia de Souza Lima, deputy director of the Global Network for Neglected Tropical Diseases says the new funding streams will guarantee that NTD programmes outlive traditional support (a large proportion from philanthropic foundations) but she concedes it also makes them susceptible to leadership change – although recent elections in Brazil and Nigeria suggest this hasn’t been the case.

Sunday, 19 July 2015

Article - Why re-think retail? Consumer expectations are changing

The blog was first publshed here on Thoughtworks by Dianne Inniss

We explored why retailers need to evolve, and what they should consider in response. How they respond tactically will vary by retailer, but here’s some food for thought

Why Re-think Retail? Consumer Expectations are Changing

Consumers are making their voices heard like never before. Here's what they're asking for:

- Immediacy: Like the fictitious Veruca Salt. consumers are saying “I want it now”. One hour Amazon delivery, Uber on demand and streaming media are all responses to - as well as drivers of - this demand for immediate gratification. And delivery expectations will only continue to accelerate.

- Personalization: Consumers are saying “I want what I want.” They are expecting more personalized and customized services that cater to them as individuals. Whether it is personal stylist recommendations from StitchFix or Le Tote, custom portfolios and investment products from online financial advisors or artisanal coffee at their local cafe, consumers expect retailers and other service providers to deliver solutions that are uniquely targeted to them and their needs.

- Ubiquity: Consumer are saying “I want it wherever and - however - I want it.” Although the term omni-channel is quickly becoming hackneyed from overuse, consumers do want to be able to use whatever channel they want, in the ways they want, at the time that best suits them, not the retailer. They also want to conduct transactions on their own terms, defining how they want retailers to interact with them (from full service to completely self-service) at any given time.

- Information Control: Consumers are saying “I have all the information I need… now I want to be edu-tained.” Consumers are inundated with information. Brands and retailers no longer define themselves. Rather, they are being defined by customers who have access to peer reviews, blog posts and more information than ever before. Given the overload of information, consumers are looking for retailers to help make sense of it all… and to cut through the clutter by entertaining them and keeping them engaged.

- Congruence: Customers want their retail experience to fit into the broader context of their lives, and to be seamless across channels. They want their service providers to recognize them no matter where they enter a transaction or how they choose to interact. Put simply, they are saying “I want a unified experience.”

Implications - What Consumers Need

Given these changing expectations, retailers must provide customers with solutions that address their well-defined needs:- Context – “Understand me where I am. Fit into what I am trying to do.”

- Empowerment – “Give me the tools to be a smarter consumer, and to lead a better life.”

- Engagement – “Entertain me; my attention span is short and lots of people are competing for my attention and my time.”

What to Do About It: Retail Response

We think that the way to address these needs is to bring disruption to the retail value chain. As consumers interact with retailers, many incremental steps add value to or subtract value from the experience. Disruption is about increasing the ratio of value-adding elements throughout the path to purchase.We propose that there are three possible strategic choices when creating disruption to drive value- Disrupt the product delivery value chain – Find ways to reduce the non-value-adding steps between the time a customer identifies a need and the time that the customer uses the product which addresses that need. For example, Amazon Dash allows customers to order certain products with the touch of a button as soon as they realize they need them.

- Disrupt the customer experience value chain - Understand customers’ transactions within the context of their whole lives, and address the broader set of needs beyond any individual transaction. For example, ALDO uses “look books” at the point of purchase to help customers understand how a pair of shoes might into a complete wardrobe, or work for multiple different wearing occasions.

- Disrupt the retail model value chain – Challenge the notion of what it means to be a retailer. This might mean becoming a clearinghouse for consumer-to-consumer transactions and/ or expanding the definition of retail to create new means of entertainment and engagement. Domino’s Pizza Mogul program in Australia has managed to do both.

These options provide an initial framework. Each retailer needs to tailor its response with an approach that is anchored in its own unique brand promise. Couple this with investments in the business processes and enabling technology to create strategic differentiation, and retailers will open a host of new ways to address changing customer expectations.- Context – “Understand me where I am. Fit into what I am trying to do.”

Article - Oversimplifying behaviourial science

Why are simplistic solutions dangerous when addressing complexity? Do they promote simplified and lazy thinking? Do they result in linear solutions based on 'low-hanging fruit' for complex problems?

Does the new found energy and excitement around behaviourial science, psychology and marketing for selling products (both in wealthy consumer driven markets as well as in low-income bottom-of-the-pyramid markets) run the same risks?

This blog post was originally published here by Jesse Singal

Here's an excerpt.

Does the new found energy and excitement around behaviourial science, psychology and marketing for selling products (both in wealthy consumer driven markets as well as in low-income bottom-of-the-pyramid markets) run the same risks?

This blog post was originally published here by Jesse Singal

Here's an excerpt.

"Although this product sounds like a fun idea, I’d worry that it could be distracting for drivers and it’s misleading to cite these rather complex and nuanced studies as evidence that looking at a smiley emoticon will make us all happier on the road," he concluded.

So no, MotorMood isn’t scientifically proven. But why should it be? It’s a light-up smiley face! Either people will like it and support it and buy it, or they won’t. Science shouldn’t have anything to do with it.

I’m only picking on this one Kickstarter because it’s a particularly silly example, and because this style of claim is so common right now. The emails arrive daily with the expectation that Science of Us and, presumably, the dozen other sites a given company is pitching, will breathlessly report shaky scientific claims that exist solely to prop up or draw attention to a given product or company.

This is a waste of everyone’s time, and in the long run it makes it hard for people who don’t think or write about this stuff for a living to understand what scientific claims really are, and what making and testing them entails.Surely there’s enough room in the world for actual, real-life science, and for products that are just fun (or stupid, depending on your opinion) but don’t need science’s imprimatur.

In other words, there’s no need to drag behavioral science into areas where it doesn’t belong. Like, you know, light-up smiley faces on Kickstarter.

Labels:

article,

behaviour,

change,

incentives,

market,

policy,

practitioners,

systems

Thursday, 16 July 2015

Article - UK supermarkets criticised over misleading pricing tactics

Great steps forward in the UK. Helping consumers feel justified in their feelings of anxiety, confusion and mistrust. I know in the past, supermarket managers have hidden behind trading standards and claimed that their price tactics are in line with the rules and fully endorsed by the trading standards office.

And, this argument is very relevant everywhere where are market systems at work!

When working in 'retail' as a market system intervention, one thing that development projects need to remember is their role in market regulation. This means the policies and institutions and an adequate oversight function in the system to curtail predatory, confusing, misleading behaviour by retailers. Including agro-inputs firms (agrovets), animal and human health service providers, small grocery shops for the urban or rural poor etc...

The article was originally published here on the Guardian website.

UK supermarkets criticised over misleading pricing tactics

http://www.theguardian.com/business/2015/jul/16/uk-supermarkets-criticised-misleading-pricing

And, this argument is very relevant everywhere where are market systems at work!

When working in 'retail' as a market system intervention, one thing that development projects need to remember is their role in market regulation. This means the policies and institutions and an adequate oversight function in the system to curtail predatory, confusing, misleading behaviour by retailers. Including agro-inputs firms (agrovets), animal and human health service providers, small grocery shops for the urban or rural poor etc...

The article was originally published here on the Guardian website.

UK supermarkets criticised over misleading pricing tactics

Rebecca Smithers Consumer affairs correspondent

Thursday 16 July 2015 09.09 BST

The competition regulator has criticised the UK’s leading supermarkets over their pricing, after a three-month inquiry uncovered evidence of “poor practice that could confuse or mislead shoppers”.

The Competition and Markets Authority stopped short of a full-blown market investigation but has announced a series of recommendations to bring more clarity to pricing and promotions to the grocery sector.

It plans to work with businesses to cut out potentially misleading promotional practices such as “was/now” offers, where a product is on sale at a discounted price for longer than the higher price applied. It also wants guidelines to be issued to supermarkets and has published its own at-a-glance guidance for consumers.

The investigation by the CMA was launched following a “super-complaint”lodged by the consumer group Which? in April, which claimed supermarkets had duped shoppers out of hundreds of millions of pounds through misleading pricing tactics.

Which? submitted a dossier setting out details of “dodgy multi-buys, shrinking products and baffling sales offers” to the authority, saying retailers were creating the illusion of savings, with 40% of groceries sold on promotion. Supermarkets were fooling shoppers into choosing products they might not have bought if they knew the full facts, it complained.

The supermarket sector was worth an estimated £148bn - 178bn to the UK economy in 2014.

In its formal response to the super-complaint, the CMA said the problems raised by the investigation were “not occurring in large numbers across the whole sector” and that retailers were generally taking compliance seriously. But it admitted more could be done to reduce the complexity in the way individual items were priced, particularly with complex ‘unit pricing’.

We have found that, whilst supermarkets want to comply with the law and shoppers enjoy a wide range of choices, with an estimated 40% of grocery spending being on items on promotion, there are still areas of poor practice that could confuse or mislead shoppers. So we are recommending further action to improve compliance and ensure that shoppers have clear, accurate information.”Nisha Arora, the CMA’s senior director, consumer, said: “We welcomed the super-complaint, which presented us with information that demanded closer inspection. We have gathered and examined a great deal of further evidence over the past three months and are now announcing what further action we are taking and recommending others to take.

Richard Lloyd, the executive director of Which?, said: “The CMA’s report confirms what our research over many years has repeatedly highlighted: there are hundreds of misleading offers on the shelves every day that do not comply with the rules.This puts supermarkets on notice to clean up their pricing practices or face legal action.

“Given the findings, we now expect to see urgent enforcement action from the CMA. The government must also quickly strengthen the rules so that retailers have no more excuses. As a result of our super-complaint, if all the changes are implemented widely, this will be good for consumers, competition and, ultimately, the economy.”

The CMA has been in close contact with retailers cited in the dossier, asking them for explanations for the misleading pricing and promotions. For the first time in its history, it has used social media including Twitter and Facebook to get more consumer and focus group feedback.

This is only the sixth time Which? has used its super-complaint power since it was granted the right in 2002. It last issued a super-complaint in 2011 when it asked the Office of Fair Trading (OFT) to investigate excessive credit and debit card surcharges. The OFT upheld its complaint. The right to make a super-complaint to the CMA or an industry regulator is limited to a small number of consumer bodies such as Which? and Energywatch. After Which? submitted its dossier to the CMA, the regulator had 90 days in which to respond. Which? said more than 120,000 consumers had signed a petition supporting the super-complaint and urging the CMA to take action.

A decade ago Citizens Advice helped bring the payment protection insurance scandal to public attention by lodging a super-complaint with the now-defunct Office of Fair Trading.

http://www.theguardian.com/business/2015/jul/16/uk-supermarkets-criticised-misleading-pricing

Labels:

article,

behaviour,

change,

incentives,

learning,

market,

practitioners,

retail,

systems

Article - Are we spoiling the private sector?

This blog was originally published here on the SEEP MaFI website.

Are We Spoiling the Private Sector?

by Md. Rubaiyath Sarwar in 2012

"As market facilitators, we strive to make the market inclusive...facilitate some small changes with the hope that the market system will open up to the poor! And we work with our ever so accommodating partners-more often than not lead firms. In the process, we keep on knocking from door to door, asking the private sector if they are willing to partner with us. And then, we negotiate, select the partners and implement our interventions. The interventions fetch excellent results. So much so that we do the same thing with the same partner in a larger scale. We call it replication. And then we involve more partners to do the same thing. We call it scale up. In some cases we say no to our beloved partner as we believe we have solved the market problem. But to our surpise, few months later, we see our partner doing almost the same thing with another project funded by another donor. Do we see another form of distortion taking place? Aren't we making ourselves too dependent on the lead firms? Why are our interventions often skewed towards the lead firms? What about other market system actors which include- civil society, professional associations, the government, the NGOs, cooperatives...? Do we always need to have commercial incentives to have sustainable impacts on scale?"

Are We Spoiling the Private Sector?

by Md. Rubaiyath Sarwar in 2012

"As market facilitators, we strive to make the market inclusive...facilitate some small changes with the hope that the market system will open up to the poor! And we work with our ever so accommodating partners-more often than not lead firms. In the process, we keep on knocking from door to door, asking the private sector if they are willing to partner with us. And then, we negotiate, select the partners and implement our interventions. The interventions fetch excellent results. So much so that we do the same thing with the same partner in a larger scale. We call it replication. And then we involve more partners to do the same thing. We call it scale up. In some cases we say no to our beloved partner as we believe we have solved the market problem. But to our surpise, few months later, we see our partner doing almost the same thing with another project funded by another donor. Do we see another form of distortion taking place? Aren't we making ourselves too dependent on the lead firms? Why are our interventions often skewed towards the lead firms? What about other market system actors which include- civil society, professional associations, the government, the NGOs, cooperatives...? Do we always need to have commercial incentives to have sustainable impacts on scale?"

Over the last decade we have observed increasing donor investment on market development projects for ‘large scale,’ ‘systemic ‘ and ‘sustainable change’ in agricultural and industrial sectors in Africa, South Asia and South East Asia. The projects proved that the donors can get better value for their investment if the private sector is attracted to invest on the interventions. More importantly, the partnership between the private sector and the project on cost sharing basis evolved as a principle tool to reposition development projects from being providers of critical services to being facilitators of the services. I have been a direct participant in this paradigm shift and evolved from being a project manager to becoming a technical advisor and evaluator of market development projects in agricultural, industrial and health sectors in several countries that include Bangladesh and Nigeria, the two hotspots for market development projects in the world.

As my roles shifted and my exposure expanded across different sectors in different countries and contexts, I observed an alarming trend. It was becoming increasingly evident that (i) market development and support to lead firms was becoming increasingly synonymous (ii) there were projects inThe question attracted wide range of participants contributing to a technically rich discussion. Contributors included Mary Morgan-Inclusive Market Development Expert, Scott Merrill- Independent Consultant, Marcus Jenal, Specialist on Systemic Approaches for Development and James Blewett, Director of Markets, Enterprise and Trade Division at Landell Mills Ltd. All the contributors shared the feeling that indeed there is a risk that market development projects, if not carefully managed, can lead to a new form of market distortion where the private sector become reliant on donor funds. However, they also reiterated the importance and significance of the collaboration with the lead firms and suggested several approaches that could mitigate the risk of the private sector becoming reliant on donor funds.

Mary suggested that partnerships work when the disparate goals of the private sector (making profits), vulnerable and poor producers (being able to produce and sell their produce at an acceptable price) and the development projects (increasing income and employment for the poor) converge towards the overall goal of inclusive market development (sustainable and systemic change in the market for employment and income generation of the poor). While acknowledging the potential pitfall of partnerships, Mary pointed out that the risk might be higher in their absence. She contributed further to the discussion by raising the point that often the support provided by the projects is much too heavy for the private sector to deliver once project support is withdrawn. As evidence, she cited a case involving Wal-Mart and Mercy Corps in an intervention on developing an inclusive supply chain for Wal-Mart in Guatemala.

The questions raised by Mary were addressed by Scott who argued that the risk of distortion is high when the projects fail to adopt good practices for partnerships. He proposed that instead of pushing the private sector towards the partnership, the development projects should seek to pull the private sector towards the development goal by soliciting proposals from the lead firms. He suggested that we should be careful with how we use the term ‘partnership’ since it could be interpreted as the lead firms being subcontractors or sub-grantees. Scott emphasized on the need to establish objective selection criteria, conduct due diligence and structure relationships with lead firms to ensure sustainability of the interventions. Scott proposed to support the lead firms to develop a business plan so that the commercial benefit from the intervention could be laid out in details prior to the inception of the intervention. This could ensure that the firm owned the development activities and continued to deliver the service after the project support was withdrawn.

James Blewett reflected on his experience in managing a challenge fund project in Afghanistan and argued that challenge funds reduce the risk of distortion in private sector engagement since it seeks to proactively engage the prospective grantees (which include lead firms) in design, co-investment and management of the interventions. He also suggested the use of financial modeling tools used by investment projects to determine ‘tipping points’ so that the project’s financial contribution to the intervention is just enough to incentivize the private sector to address the investment risk associated with the intervention.

A very important contribution to the discussion came from Marcus who suggested that before deciding on the financial arrangements and technical support, the projects should ask why the private sector is not investing on the intervention on its own if it made commercial sense. He advocated for ‘form follows function’ approach and suggested that the projects should partner with lead firms when it is clear that the vulnerable will benefit from the partnership. Marcus argued that the lead firms often do not invest to reach out to the vulnerable not because they haven’t seen the opportunities, but because of a dysfunctional regulatory system, which according to him is the systemic constraint that needs to be tackled.

From the discussion it was evident that while the need for collaboration with the private sector is real, there needs to be further push from the donors, development projects and practitioners to ensure good practices and reduce risk of distortion in the market systems due to over-engagement with the private sector. The discussion also revealed that there are good practices and models that are being followed and discussion around these models could help market development practitioners to be better able to answer to why they have partnered with the lead firm, what support (financial and technical) they should be providing and why, and finally, how the lead firm is expected to sustain the intervention after the project support is withdrawn. the same region or country competing for partnership with same lead firms (given that there are not too many in the country that qualifies to become a partner) (iii) the proliferation of market development projects in the same sector led to increasing number of lead firms receiving funds from them that ended up subsidizing their R&D, distribution and marketing costs and (iv) it was becoming difficult to evaluate whether the intervention resulted in systemic change since the lead firms continued to replicate the intervention with funds from other projects once the support from the original project was withdrawn. This prompted me to ask the members of the Market Facilitation Initiative (MaFI) whether they shared the feeling that probably it is time for us market development practitioners to be a little cautious when we approach lead firms.

Wednesday, 15 July 2015

Do housing vouchers work for poor people?

One way of reducing poverty is by increasing the ability to pay. And one mechanism is to give cash directly to low-income people either as cash itself or through a voucher system.

This piece of research from the Urban Institute looks at using vouchers (i.e. one type of conditional cash transfers) to help families pay for housing. The theory goes that helping families pay rent (the largest part of household budgets), they are less likely to experience economic stress and food insecurity.

The research is very optimistic about vouchers. But, it is very important to point out the potential impacts of using vouchers as welfare support on the system.

This piece of research from the Urban Institute looks at using vouchers (i.e. one type of conditional cash transfers) to help families pay for housing. The theory goes that helping families pay rent (the largest part of household budgets), they are less likely to experience economic stress and food insecurity.

The research is very optimistic about vouchers. But, it is very important to point out the potential impacts of using vouchers as welfare support on the system.

- Vouchers can create perverse incentives. Low-income families may go to shelters in order to be eligible for vouchers. This points to a need to identify the deeper problem within the system. Families that leave housing for shelters to get vouchers to go back to housing must be thinking about things that we can't see. What are the incentives to drive this kind of behaviour? Who is making that decision to move? Is it the family career or is there pressure coming from elsewhere? What is the quality of the housing? What makes shelters (and vouchers) so attractive compared to housing?

- Vouchers can create free rider effects and increase welfare and reduce employment. However, this is a simplistic understanding of the problem. The article points out that we should also keep in mind that helping families get jobs and better-paying jobs is not just about getting rid of disincentives to work; it is also about opportunities for people to build job skills, and access basic benefits, such as health insurance.

- Vouchers can be expensive. A systemic analysis would look at the costs of different options and determine if vouchers is the most value-for-money considering the systemic constraints. Additional information would be needed to build a value/cost model: How long do families remain on vouchers? How do the ongoing costs of vouchers compare with not providing vouchers (i.e. families cycling in and out of shelter)? How do count families that cycle in and out of shelter (i.e. churn)?

The dangers of of the 'cash transfer magic bullet'

Cash transfers, conditional or not, are a particularly dangerous movement in development.

The research from Harvard, MIT, NPR on cash transfers has been often cited in the media. But, it is clear that the the cash transfer mechanism is a very limited and is a short-term stimulus that does not address systemic failures that keep people poor. Could this be another magic bullet that make donors feel good about giving money? Won't money just flood the systems but play no role in building systems? How is this sustainable or scaleable beyond any donor handout?

It is the system that causes poverty, and not, as is assumed under the cash transfer paradigm, people and people's willingness and ability to pay. To take this one step further it is the weak poorly-functioning system for goods, services, information, knowledge that causes poverty. if for example, there are medicines available for poor people to buy, the systemic problem is actually that medicines are not well-distributed and clearly branded with a system for verification so that counterfeits cannot creep in. If there are agents/traders/salespeople/distributors working for the big pharmas, the question is always: what are they incentivised to do? Is it to push products for commission? If so, what will the effect be on the quality of information that goes out to people on what they should buy? Who can poor people go to make sure their ability to spend isn’t subsumed by their inability to get a good quality product?

In weak systems, there are systemic constraints that trap poor people in a cycle of no/bad/sub-optimal investment. They also have no 'voice' to complain, protest, influence, push up quality. Poor people are ‘voiceless’. Cash transfers simple result in money in the pocket but no voice or influence.

Labels:

behaviour,

change,

economics,

failure,

finance,

incentives,

market,

policy,

practitioners,

systems

Tuesday, 14 July 2015

Why employee rankings can backfire

This NY Times article talks about how employee rankings to drive up performance can actually backfire.

In the workplace, promoting competition between individuals

can have several effects. Instead of driving up performance, in an context that

needs people working in teams with high levels of collaboration, there can be several

opposite effects. One tool for promoting competition in order to improve

performance is through HR assessments and ranking. When ranked in a list,

people can exhibit the following behaviour:

- Some feel positive, and strive to do better in order to increase their rank or to stay at the top

- Some feel demoralised at the valuation of their performance, and reduce performance and fall down the table

- Some feel content and stick with what they are doing, thus maintaining performance and rank position

- Some feel suspicious and have less trust in management and the company, which may result in reducing performance or even a tendency to sabotage the process or the company

Source: http://www.nytimes.com/2015/07/12/business/why-employee-ranking-can-backfire.html?_r=0

Article - Digital finance for smallholder farmers - a systemic approach

This USAID Microlinks article describes a systemic approach to building financial systems for digital-based smallholder farmer finance. This approach is naturally scalable as it has the in-built mechanisms for growth.

These interventions use the following design tactics:

These interventions use the following design tactics:

- Behaviour change principles such as, features and incentives to make it easier for people to adopt a new practice for the first time

- Multi-level design - digital services can both bring in new behaviours as well as make existing good practice more efficient and automated and easier to stick to

- Savings and insurance services for resilience and long-term sustainability

Source: How Digital Financial Services Can Meet The Financing Demands Of Smallholder

Farmers, LIZ DIEBOLD, Agriculture Finance And Investment

Lead, NANDINI HARIHARESWARA, Senior Digital Finance Advisor, And HARSHA KODALI, Agricultural Finance Specialist PUBLISHED ON JUNE 16, 2015,

AVAILABLE AT WWW.MICROLINKS.ORG/BLOG/HOW-DIGITAL-FINANCIAL-SERVICES-CAN-MEET-FINANCING-DEMANDS-SMALLHOLDER-FARMERS

Labels:

article,

behaviour,

change,

finance,

ICT,

incentives,

market,

practitioners,

systems

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)