Great steps forward in the UK. Helping consumers feel justified in their feelings of anxiety, confusion and mistrust. I know in the past, supermarket managers have hidden behind trading standards and claimed that their price tactics are in line with the rules and fully endorsed by the trading standards office.

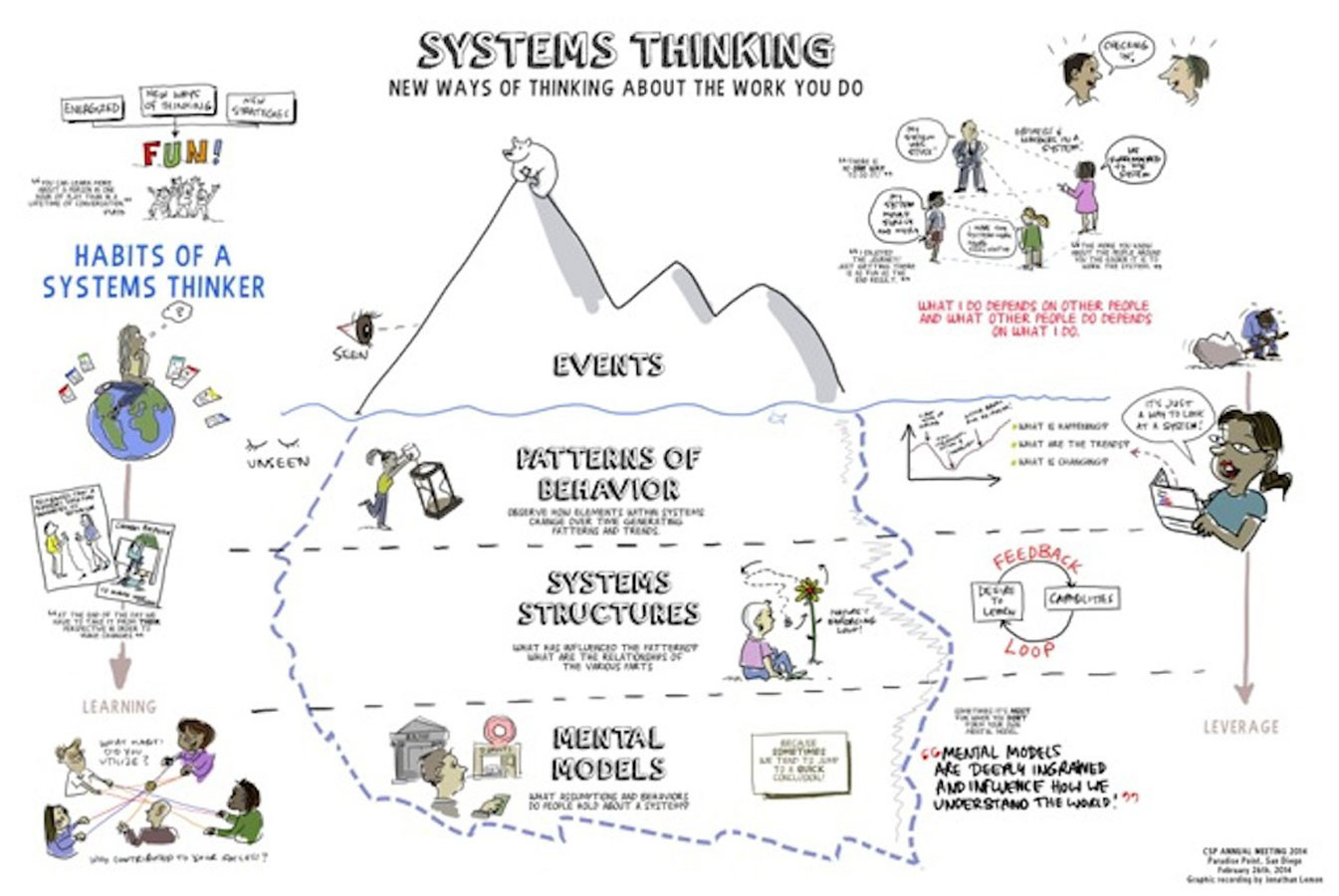

And, this argument is very relevant everywhere where are market systems at work!

When working in 'retail' as a market system intervention, one thing that development projects need to remember is their role in market regulation. This means the policies and institutions and an adequate oversight function in the system to curtail predatory, confusing, misleading behaviour by retailers. Including agro-inputs firms (agrovets), animal and human health service providers, small grocery shops for the urban or rural poor etc...

The article was originally published here on the Guardian website.

UK supermarkets criticised over misleading pricing tactics

Rebecca Smithers Consumer affairs correspondent

Thursday 16 July 2015 09.09 BST

The competition regulator has criticised the UK’s leading supermarkets over their pricing, after a three-month inquiry uncovered evidence of “poor practice that could confuse or mislead shoppers”.

The Competition and Markets Authority stopped short of a full-blown market investigation but has announced a series of recommendations to bring more clarity to pricing and promotions to the grocery sector.

It plans to work with businesses to cut out potentially misleading promotional practices such as “was/now” offers, where a product is on sale at a discounted price for longer than the higher price applied. It also wants guidelines to be issued to supermarkets and has published its own at-a-glance guidance for consumers.

The investigation by the CMA was launched following a “super-complaint”lodged by the consumer group Which? in April, which claimed supermarkets had duped shoppers out of hundreds of millions of pounds through misleading pricing tactics.

Which? submitted a dossier setting out details of “dodgy multi-buys, shrinking products and baffling sales offers” to the authority, saying retailers were creating the illusion of savings, with 40% of groceries sold on promotion. Supermarkets were fooling shoppers into choosing products they might not have bought if they knew the full facts, it complained.

The supermarket sector was worth an estimated £148bn - 178bn to the UK economy in 2014.

In its formal response to the super-complaint, the CMA said the problems raised by the investigation were “not occurring in large numbers across the whole sector” and that retailers were generally taking compliance seriously. But it admitted more could be done to reduce the complexity in the way individual items were priced, particularly with complex ‘unit pricing’.

We have found that, whilst supermarkets want to comply with the law and shoppers enjoy a wide range of choices, with an estimated 40% of grocery spending being on items on promotion, there are still areas of poor practice that could confuse or mislead shoppers. So we are recommending further action to improve compliance and ensure that shoppers have clear, accurate information.”Nisha Arora, the CMA’s senior director, consumer, said: “We welcomed the super-complaint, which presented us with information that demanded closer inspection. We have gathered and examined a great deal of further evidence over the past three months and are now announcing what further action we are taking and recommending others to take.

Richard Lloyd, the executive director of Which?, said: “The CMA’s report confirms what our research over many years has repeatedly highlighted: there are hundreds of misleading offers on the shelves every day that do not comply with the rules.This puts supermarkets on notice to clean up their pricing practices or face legal action.

“Given the findings, we now expect to see urgent enforcement action from the CMA. The government must also quickly strengthen the rules so that retailers have no more excuses. As a result of our super-complaint, if all the changes are implemented widely, this will be good for consumers, competition and, ultimately, the economy.”

The CMA has been in close contact with retailers cited in the dossier, asking them for explanations for the misleading pricing and promotions. For the first time in its history, it has used social media including Twitter and Facebook to get more consumer and focus group feedback.

This is only the sixth time Which? has used its super-complaint power since it was granted the right in 2002. It last issued a super-complaint in 2011 when it asked the Office of Fair Trading (OFT) to investigate excessive credit and debit card surcharges. The OFT upheld its complaint. The right to make a super-complaint to the CMA or an industry regulator is limited to a small number of consumer bodies such as Which? and Energywatch. After Which? submitted its dossier to the CMA, the regulator had 90 days in which to respond. Which? said more than 120,000 consumers had signed a petition supporting the super-complaint and urging the CMA to take action.

A decade ago Citizens Advice helped bring the payment protection insurance scandal to public attention by lodging a super-complaint with the now-defunct Office of Fair Trading.

http://www.theguardian.com/business/2015/jul/16/uk-supermarkets-criticised-misleading-pricing